I previously worked as a researcher in academia for over 12 years. My research took me into diverse fields of study including marine mammal biology, computational biology, protein folding, artificial life, complex systems analysis, plant biology, genomics, marine molecular developmental biology and RNA biology.

In recent years I started working on an independent open science research project in my spare time. You can follow my open research journey here.

Read on to learn about my previous research on the fascinating genome of the zooplankton, Oikopleura dioica.

You can also read about my PhD research in the fields of complex systems and artificial life.

My list of academic publications is here.

Developmental Genomics#

Genome-environment interactions#

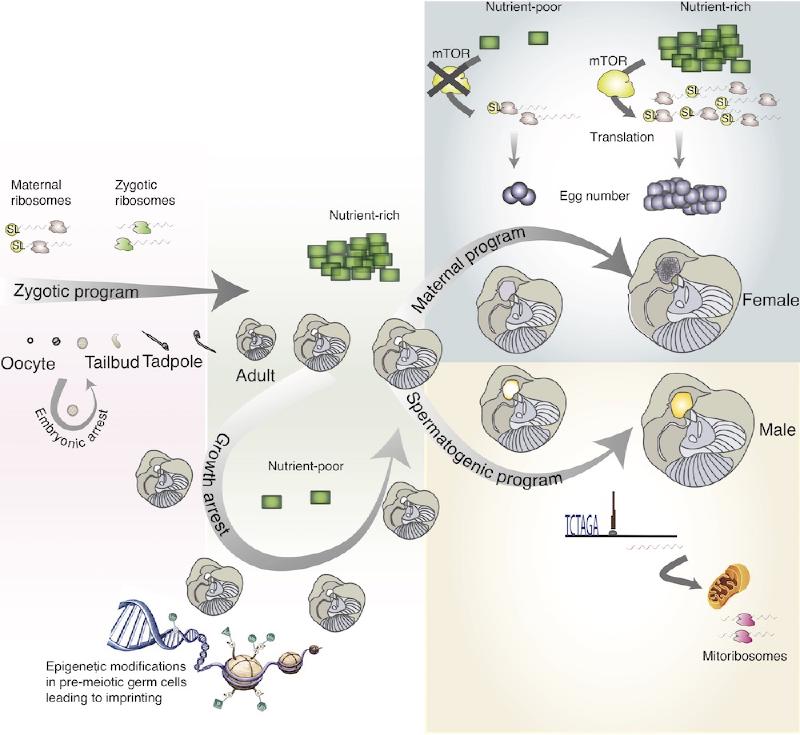

A complex multicellular organism develops from an egg by following the instruction manual from its parents that it keeps in its genome. The information is all there waiting to be read by the molecular machinery of the egg and the DNA manual is copied into every cell. But once development gets underway, the same instructions are not read by every cell. The genome is subject to constant re-wiring — muting some parts and activating others — to bring about critical transitions at specific times and in specific places.

Back in academia, my main research interest was in trying to understand how the genome is rewired to orchestrate developmental transitions and how this rewiring responds to changes in the environment and determines alternate life history strategies.

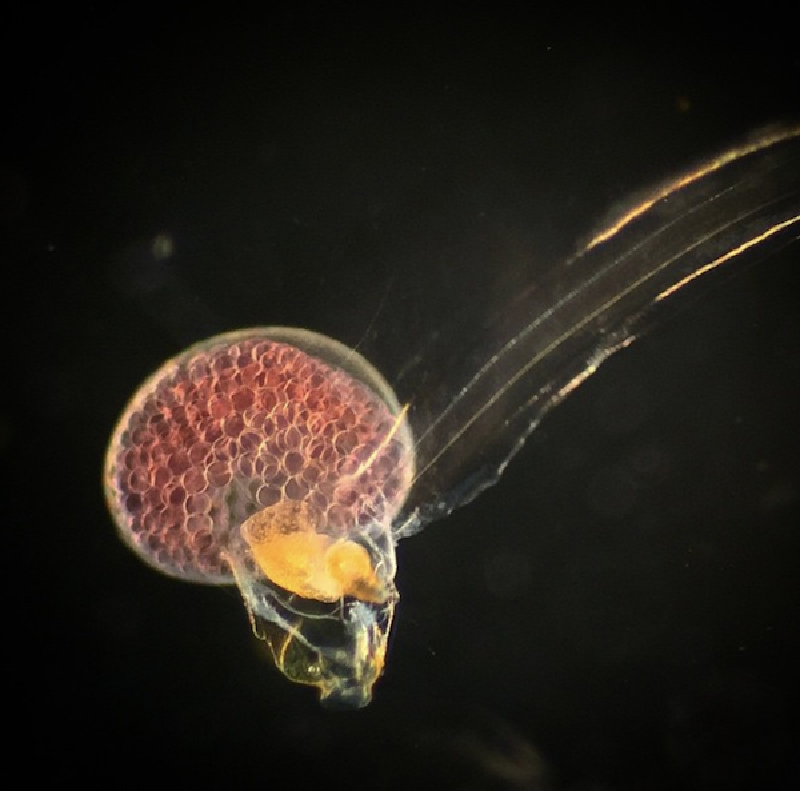

Oikopleura dioica#

This zooplankton, living in oceans across the globe, is among the closest living relatives to vertebrates. It has a small, shuffled genome and it builds complex filter-feeding houses that it sheds several times a day – making marine snow and capturing carbon in the process.

Oikopleura is a fascinating animal for studying how the genome is rewired during development.

I spent 8 years working on it as a postdoctoral researcher at the CBU and the Sars Centre for Marine Molecular Biology (now the Michael Sars Centre) in Bergen Norway.

You can see a summary of my areas of research in Oikopleura in the figure below. Read on for the details.

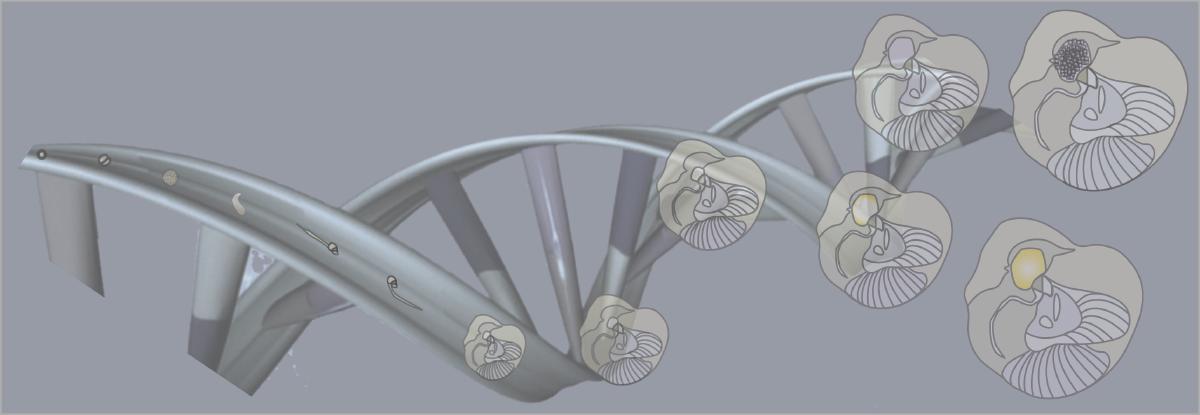

RNA trans-splicing as a regulator of egg numbers#

My favourite topic!

Oikopleura has a very special way of processing many of the messenger RNA molecules it transcribes from its genes: it adds an extra sequence to one end. This is called RNA trans-splicing. Amazingly, despite several decades of research into the few animals that do this, the function of the extra sequence was largely mysterious.

I developed and tested the hypothesis that RNA trans-splicing works as a way of regulating the egg numbers in Oikopleura according to how much food the zooplankton has in its environment via an ancient molecular regulator of growth. This regulation might be helping the population respond to algal blooms in the ocean.

This goes beyond the population levels of Oikopleura: it’s a fascinating example of how the molecular blueprint of life can receive cues from the wider environment.

You can read more about this in three of my publications on the topic: the first one shows that most of the genes that have this extra tag are maternal (i.e. stocked in eggs); the second is a commentary that fleshes out the hypothesis in more detail; the third puts the hypothesis to the test.

Environmental cues for exiting growth arrest#

In the lab, if you culture Oikopleura at high enough density and restrict their food they will arrest their development right before they start their reproductive program. They stay in stasis until conditions are better for growth. I studied what environmental triggers cause them to leave stasis, how this is controlled at the level of the genome and how it is related to RNA trans-splicing.

You can read more about this in two of my papers on trans-splicing here and here.

Promoter codes for developmental transitions#

When the cellular machinery has to read the genome it needs to know what parts to read and where to start. Promoters are landing sites in the DNA for this machinery and they are written into the DNA using special codes that mark what genes should be switched on and when.

I studied these codes in Oikopleura and used machine learning to classify them. You can read more about how in this paper.

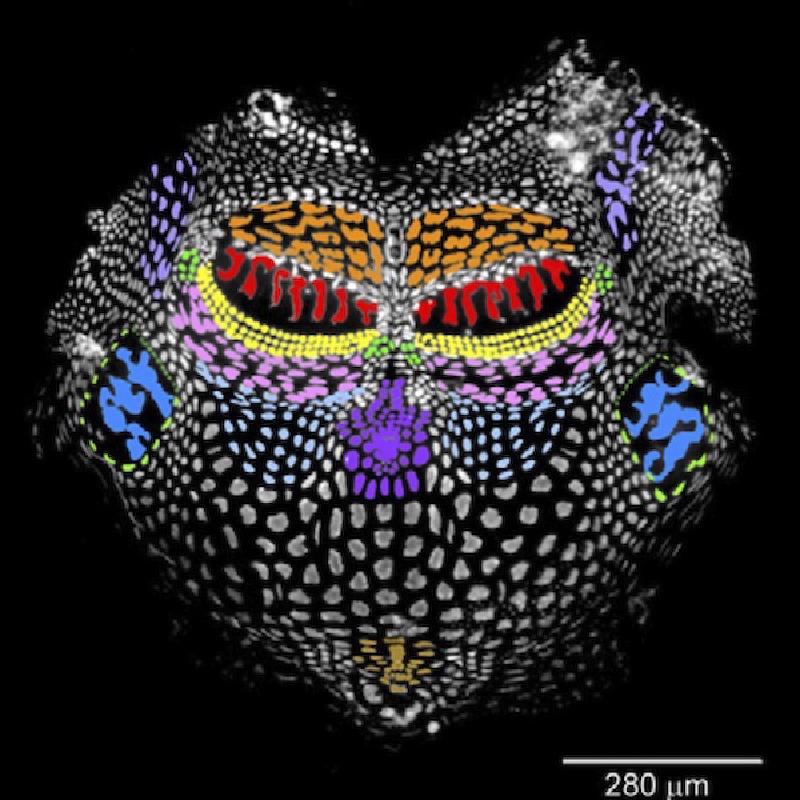

Chromatin states#

DNA is packaged in the cell using proteins called histones. Histones also have a code that tells the cellular machinery what parts of the DNA should be opened up and read and which parts should be closed off and silenced. I worked on deciphering this code and how it differs in male and female Oikopleura. You can read more details here.

Genome evolution and house building#

One of the most fascinating things about Oikopleura is that it builds this beautifully complex ‘house’ around itself for filter-feeding algae from seawater. It is the possession of this ‘house’ that gave Oikopleura its name (oiko comes from the greek word for house). Every few hours, Oikopleura sheds its house and builds a new one. The discarded houses sink through the ocean as marine snow and trap carbon in the process.

Oikopleura builds its houses using special cells around its body that, together, secrete a particular pattern of molecules that create the different chambers and funnels of the house.

Some of these molecules, called oikosins, are not found in other groups of animals. You can read more about them in this paper.